A gathering in the central place of the orange revolution, the Independence Square (Maidan), Kiev. [source] [credits]

On December 26, 2004, citizens of Ukraine voted to elect their

president. Several thousand international observers were accredited for

the

event. This web page documents what I saw as an observer.

All photos in this document are

clickable (click to enlarge).

In recent history, Ukraine has only been an independent nation since 1991. From 1945 to 1991, the entire territory of Ukraine was part of Soviet Union, and was subject to Moscow's totalitarian rule. As a result of Soviet heritage, powerful groups stemming from Russian and Ukrainian former nomenklatura retained a lot of power over Ukraine, and, in 2004, were not willing to accept the election of a president unconnected with them. This political context influenced heavily the election.

In this election, the two major candidates were the pro-Russian and pro-Putin prime minister Viktor Yanukovych (Віктор Янукович), and the leader of the opposition Viktor Yushchenko (Віктор Ющенко), attached to the independence of Ukraine and to western-style democracy and liberal capitalism.

The election was initially held on October 31 and on November 21 (run-off). During the campaign, government-controlled television strongly supported Yanukovych. During the election, the secrecy of ballots was often violated, and voters were intimidated. Massive fraud was organized: according to Yushchenko's supporters, fraud deprived Yushchenko of 3 million votes. Yushchenko was poisoned during the presidential campaign, and spent several weeks struggling for life instead of campaigning.

On November 24, the Central Electoral Commission of Ukraine declared Yanukovych the winner of the November 21 vote. In response, several foreign governments strongly criticized the election, and hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians protested (these protests are commonly called Orange Revolution).

A gathering in the central place of the orange revolution, the Independence Square (Maidan), Kiev. [source] [credits]

The Ukrainian government did not use force to suppress the protests (apparently, part of armed forces was on the side of the protesters, making the use of force virtually impossible). Instead, negotiation started on November 26 between the outgoing president Kuchma, and Yushchenko. The negotiation involved high-ranking representatives of four foreign powers (the European Union, Poland, Lithuania and Russia).

On December 3, the Supreme Court of Ukraine acknowledged that a host of gross irregularities had accompanied the November 21 vote, annulled the vote, and called a new vote for December 26 (see the Supreme Court findings in English, the full text of judgment in Ukrainian).

On December 8, the political solution negotiated between Kuchma and Yushchenko was implemented: officials who had participated in electoral fraud were removed from the Central Electoral Commission, and a new electoral law was enacted. The new law allowed both candidates to be represented equally in local electoral commissions, and modified many aspects of the electoral procedure in order to prevent fraud similar to the one observed on November 21.

I observed the election in Vola Kovelska (Воля Ковeльська), a village in the Volyn region (North-West of Ukraine). An overwhelming majority of Volyn inhabitants supports Yushchenko.

In Vola Kovelska, I observed no fraud, and no voter intimidation

or other bad-faith behavior connected with the election. People were

very friendly towards me. I cannot tell,

however, that the voting procedure was fully satisfying. This section

describes noteworthy aspects of the procedure.

The voting station was equipped with three voting booths. Each

had an opaque curtain. All voters used the booths to fill in their

ballots (this could appear as obvious to the Western reader, but is

noteworthy given that Ukraine is a former Soviet nation). There was a

bed in each booth; this bizarre

feature was due to the voting station being located in a dispensary.

On the right, you can see ballots in one of the ballot boxes in Vola Kovelska, during the vote. The content of several ballots is in plain view (click to enlarge the photo, and you will be able to read the content of five ballots, all five for Yushchenko; to understand how to read a ballot, read below).

To preserve voting secrecy, voters can fold their ballots. Among the ballots visible in the photo, some are not folded. Others were folded by voters, but later unfolded, and their content is visible. Additionally, two ballots are easy to distinguish from all others, because they are folded in atypical ways.

Two distinct flaws in the voting procedure are apparent here. First, folding ballots, as it is done in Ukraine, does not reliably ensure vote secrecy. The problem is exacerbated by the possibility to make video tapes of the voting process (official observers are legally entitled to do this). An observer with a video camera may exploit the unreliable way in which folding works, and record who voted for which candidate. Reportedly, this was actually done in certain voting stations during the November 21 vote.

Second, many people in Ukraine consider that vote secrecy is an individual right of the voter, not an obligation, and therefore the voter may make his ballot visible to others if he chooses to. For example, I observed several disabled persons who voted in their homes for Yushchenko (voting at home is discussed below) and, when I asked them not to show the ballot to commission members, answered "I have no fear."

I discussed the issue of secrecy with the local electoral commission, explaining that all ballots must be secret according to international standards (see for example this OSCE document). Commission members maintained firmly that secrecy is not an obligation for the voter, and therefore they have no power to force voters to fold ballots (or otherwise to keep the ballots secret).

Nevertheless, following our discussion the commission started to ask voters to fold their ballots. As a result, at noon we had the situation shown on the right: at this point, all recently casted ballots were folded. (Some ballots were still visible, in spite of being folded; this is a distinct problem.)

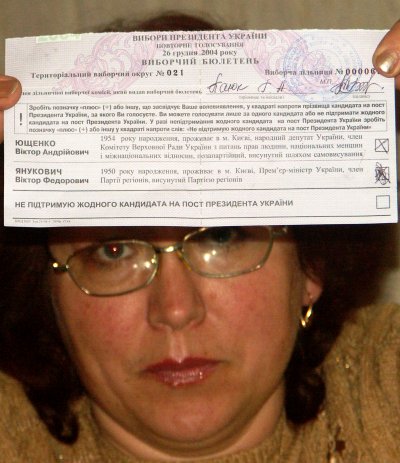

Each ballot used in the December 26 election comes with a control coupon attached (a horizontal dotted line separates the ballot from the control coupon). When the ballot is delivered to the voter, the control coupon is detached from it, and is kept as part of the voting station's documentation.

During the ballot count, an invalid ballot is displayed to the observers (the ballot is invalid because there are marks in two squares).

Both the ballot and the control coupon contain numbers identifying the voting station (in the example: 021 and 000067). When the commission delivers the ballot to the voter, the name and the signature of a member of the commission are added both to the ballot and to the control coupon. Additionally, the number and the signature of the voter are added to the control coupon (but not to the ballot).

The text accompanied by a big "!" sign instructs the voter to express his choice by making the "plus" sign (+) or another sign in the corresponding square in the ballot. Three choices are offered, in this order: Yushchenko, Yanukovych, and "I support no candidate for the office of President of Ukraine".

Control coupons: I do not understand the role of the control coupons, as they are redundant with the list of voters (a key document held by the precinct electoral commission): the coupons are filled in with information and signatures also present in the list of voters.

Features of the ballot: The numbers present on the ballot, and the name and signature of a member of the commission, are anti-fraud devices.

Specifically, one fraud method well-known in former Soviet nations consists in providing voters with forged ballots filled in in advance in favor of a given candidate. The voters are then rewarded for (or intimidated into) voting with these ballots, instead of the genuine ones. To make sure that voters actually use the forged ballots, the organizers of fraud ask them to bring back the blank, genuine ballots received at the voting station.

Numbers in the ballot significantly complicate forgery from a logistical point of view: they make it necessary to use ballots forged specifically for every given voting station, and this is more complicated than obtaining one big batch of forged ballots, and using it nationally.

The handwritten name and the signature in the ballot further complicate forgery. Unlike the production of the ballot itself, these elements are under the control of the relevant precinct electoral commission, and even if fraud organizers have access to a source of forged ballots, they still need to separately forge these elements.

Vote secrecy: Certain features of the ballot are detrimental to the secrecy of the vote. Specifically:

Two members of the commission carry the mobile ballot box from one voter's home to another, accompanied by one observer for Yanukovych (on the left), and one from Poland (behind the camera).

While not in use, the mobile ballot box was stored overhead in the voting station, next to a religious icon. The persons in front are Yuri Muzychuk, president of the commission (left), and Olga MItchyk, secretary.

In Ukraine, those who are unable to go to the voting station, have the right to vote at home. For this purpose, each voting station has a mobile ballot box, and a car at its disposal.

During the October 31 and the (later annulled) November 21 ballots, the procedure for voting at home acquired a reputation of providing a good occasion for fraud. Let us explain why.

During these two ballots, the law was not specific about the presence of observers during the vote at home, and many commissions did not allow observers to travel in the voting station's car. Voting at home was conducted by three members of the electoral commission, representing three different candidates. However, among the 24 candidates in the election, many were politically connected with the government in place, and it was easy to find three members of the commission who officially represented three different candidates, yet in reality were all connected with the government. In these conditions, fraud was not difficult to organize.

Voting at home was in fact available to anyone who requested it: no medical certificate was required, and the law provided for no verification of the voter's inability to go to the voting station. This explains why voting at home was a large-scale phenomenon, and fraud connected with it was quantitatively important.

The law of December 8, 2004 changed the situation. Under this law, one commission member for each run-off candidate is allowed to be present during vote at home. The new law only allows one mobile ballot box in each voting station (previously, multiple boxes were commonly used, further complicating the observers' work). The new law also restricts voting at home to those with the official status of severely disabled persons ("first group disability"). Thus, the scale of the procedure (and the magnitude of any fraud that could be based on it) is severely limited.

The latter restriction was judged discriminatory and annulled by the Constitutional Court on December 24. The judgment was perfectly clear by itself, but nevertheless led to much confusion: for example, on election day I was told by several persons that people with "first or second group of disability" status were now allowed to vote at home (this was not true: the judgment extended the procedure to all who declare that they need it, without regard to any official disability classification).

As a result of the confusion and of short time limits, in Vola

Kovelska the restriction

imposed by the law of December 8 was effective: those who could

have benefited from the December 24 judgment did not manage to file

the required paperwork before the December 25 noon deadline. (Note:

for an overwhelming majority of Ukrainians, Christmas is on January 7,

not

on December 25.)

The voting station's car is a Lada. The hood is open, indicating that the car is not working perfectly.

What I observed: In Vola Kovelska, twelve persons voted at home. Yanukovych and the Republic of Poland had observers in the voting station, and one observer from each group was invited to travel in the voting station's car, in addition to two members of the commission, and to the driver.

Several handicapped voters made strong anti-Yanukovych and/or pro-Yushchenko comments while voting, some did not want to observe vote secrecy and wanted to show everyone present that they voted for Yushchenko. This behavior contrasts with the atmosphere reigning in the voting station, where, as prescribed by law, almost no political statements or demonstrations were made.

I observed no violations of law connected with voting at home, except for the less-than-perfect respect of vote secrecy.

Ukrainian law allows disabled persons to vote with help from another person. This procedure can be used both at home and at the voting station. In the latter case, the person who helps a voter can enter the voting booth with him.

The law only allows a voter to receive help from a fellow voter, simultaneously present at the station for voting (or present in the voter's home). Help by other persons, especially by commission members or by observers, is not permitted, so that these persons cannot intimidate voters by offering unwelcome help. This restriction was fully respected in Vola Kovelska.

Unfortunately, the electoral commission has no reliable way to verify whether a given voter genuinely needs help. Specifically, the law requires no proof of disability and no medical certificate. This opens the way for intimidation of voters by other persons (especially relatives), who want to control their vote under the pretext of offering help.

No record is kept regarding this special procedure (the fact that a given voter received help is not recorded). Therefore, it is very difficult to assess the scale of this procedure and the magnitude of problems it can possibly lead to.

I have no reason to believe that this procedure was actually used in Vola Kovelska to exert undue control over anyone. However, for reasons stated above, I am unable to tell for sure.

The following sequence shows three features of the voting procedure:

voting at home, voting with another voter's help, and the disregard for

vote secrecy.

Voting at home begins: the disabled voter is on the left, a member of the commission is on the right (another member of the commission and two observers are also present).

The member of the commission checks the disabled voter's domestic passport [soviet name for an identity card], and looks up the voter's name in the list of voters.

For a reason unknown to me, they change their minds: another family member comes to help the voter. He signs the list of voters in place of the voter. Then, the family member fills in the ballot in presence of the voter [not recorded in order not to further diminish vote secrecy].

Then, the commission member discovers that the

control coupon was not cut off from the ballot, so she takes back the

(already filled-in) ballot, cuts off the coupon, and gives the ballot

back to the family member.

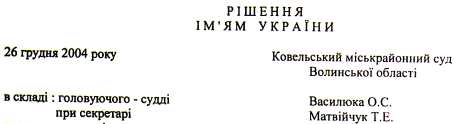

Header of a judgment ordering the

registration of a voter (click on the image to see the complete

judgment).

It was possible for voters to get registered (get added to the list of voters) during the December 26 vote. This possibility is quite extraordinary: in most countries, lists of voters are prepared and made final in advance.

Election-day voter registration could only be done by a decision of a court of justice. In Vola Kovelska, five voters were registered in this way, by judgment of the court in the nearby city of Kovel.

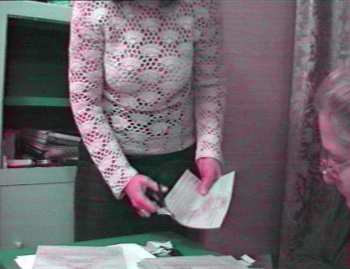

A member of the commission cuts corners off unused ballots (I beg the lady's forgiveness for showing her with her head cut off).

At the beginning of the count, all members of the commission were

asked by the president to surrender pens, to prevent ballot alteration

(reportedly, the alteration of ballots during the count was a fraud

method used in Ukraine in the October 31 and November 21 votes).

Each step in the ballot counting procedure started with the commission president reading aloud the relevant chapter of the electoral law.

The first step was performed while the ballot boxes were still sealed. It consisted in disposing of unused ballots: the ballots were counted, had their bottom-right corners cut off, and were stuffed into envelopes.

Then, the ballot boxes were unsealed, the presence of control sheets

inside was verified, and ballots were unfolded and counted (a control

sheet is inserted into each box before the beginning of the vote, and

bears the signatures of all members of the commission). Control coupons

were also counted, and the number of ballots was compared with the

number of control coupons and with the number of ballots cast according

to the list of voters. No discrepancies were found.

Then, a commission member read aloud the content of all ballots,

and

the ballots were divided into four groups: Yushchenko, Yanukovych, "I

support no candidate for the office of the President of Ukraine", and

invalid ballots. The ballots in each group were counted and re-counted,

by pack of 50 (actually, only the Yushchenko group contained over 50

ballots).

Finally, a protocol was written. All ballots were stuffed into

cardboard boxes, and the boxes were sealed. The protocol and the boxes

with ballots were sent to the territorial electoral commission.

Behind locked doors: Ballot counting in Ukraine is not done publicly. Three categories of people are allowed to be present: members of the precinct electoral commission, official observers, and accredited journalists. In Vola Kovelska, ballots were counted behind locked doors.

Each precinct electoral commission comprises 12 or 16 members (in

Vola Kovelska, there were 12 members). All these 12 or 16 people

participate in

the counting procedure, they are simultaneously performing

operations that involve touching ballots. Each candidate is allowed to

send up to four observers to watch the counting. Each news outlet can

send up to two journalists to report on it. The number of international

observers is not limited by law.

Let us note that the general public is also

excluded

from observing the vote itself, not only the ballot counting: by law,

a voter is only allowed to

remain

present at the voting station for the time necessary for voting.

Opinion: International law

and OSCE rules do not support the

presence of the general public during the counting of

ballots. OSCE even opposes the continued presence of unauthorized

persons during the vote; see this

report, item 8.6 (such presence may, apparently, have an

intimidating or propaganda effect).

I

believe, however, that excluding the public from ballot count is

unfortunate, because

actions of public authorities should, to the extent possible, be

performed in view of everyone. Acting in plain view deters officials

from improper behavior, and increases the confidence of the public in

the authorities. The presence of official observers (and the presence

of journalists, when they are indeed present) is very positive

in this regard, but the presence of the general public would be even

better.

Nationally, Yushchenko was elected with 52 % of ballots, Yanukovych received 44 % (this does not add up to 100 %, because the voters can also choose "I support no candidate").

In Vola Kovelska, the

turnover was 91.1 %. This

astonishing number

shows the great importance that Ukrainians attached to the election.

Yushchenko got 93.6 % of ballots in Vola Kovelska. This is in line with what happened nationally: in several regions (oblasti) of western Ukraine, Yushchenko got in excess of 90 % of ballots (Volyn, where Vola Kovelska is located, is the most north-western region of Ukraine, with 90.7 % of ballots for Yushchenko).

I think that intimidation had taken place on

October 31, because I

heard voters say "I

have no fear" while voting for Yushchenko on December 26 (see above); people would not say this if they had not

been pressured or intimidated, at least to some extent.

Regarding

fraud, observe that the number of ballots invalid on October 31 was

extremely high (2.6 %). I don't know what happened exactly, but at

any

rate, the number of invalid ballots would not have been so high, had

the vote being conducted properly (certain fraud methods known in

Ukraine are based on invalidating ballots during the ballot count; this

is one possible cause of the high number of invalid ballots).

| In Vola Kovelska: | October 31 | December 26 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total votes cast |

574 | (90.1

% |

turnover) | 570 | (91.1

% |

turnover) |

| Yushchenko |

453 |

(81.0 %) | 531 |

(93.6

%) |

||

| Yanukovych |

60 |

(10.1 %) | 26 |

(4.6

%) |

||

| other candidates |

41 |

(7.3 %) | - |

|||

| against all candidates |

5 |

(0.9 %) | 12 |

(2.1

%) |

||

| invalid ballots |

15 |

(2.6

% |

of valid ballots) |

1 |

(0.2

% |

of valid ballots) |

The three stickers on display in the local restaurant say,

respectively, "We will not give

Ukraine to criminals," "Ukraine

is one," and "Yushchenko, our

president."

The reference to criminals is about Yanukovych, who served jail time

twice in the past

(under Soviet rule), for serious crimes unconnected with

politics.

The "Ukraine is one" sticker can be explained as follows.

As you can see in the chart above, Ukraine was sharply divided

into pro-Yushchenko and pro-Yanukovych regions. This roughly

corresponds with

the ethnic structure of the country: most Ukrainian speakers

supported Yushchenko, and many non-Ukrainian speakers supported

Yanukovych (most of them live in Eastern Ukraine and in Crimean

Peninsula (south), and

speak Russian).

During Orange Revolution, Yanukovych attempted to start the process

of cutting off eastern, Russian-speaking regions from Ukraine. This

looked like

a realistic threat, given the situation in the neighboring countries of

Moldova and Georgia: certain Russian-speaking regions of these two

countries are de

facto independent, and

are governed by local

pro-Russian dictators.

In the past, the Volyn

region was ethnically mixed: in addition to Ukrainians it was

populated by many Poles and some Jews. From 1920 to 1939, the region

was part of the Republic of Poland

[see Wolyn

Voivodship]. Many Ukrainians did not accept this fact, and were

hostile to Poland. Rights of

ethnic Ukrainians were often not respected by the Polish government;

sometimes, the government went as far as using military force to

destroy Orthodox churches or to persuade villagers to change their

religion. Such actions stirred even more hostility from the Ukrainian

population. During World War Two,

Ukrainian forces performed ethnic cleansing operations, killing

approximately 100 000 Poles in Volyn.

In today's Volyn, I saw virtually no trace of the old ethnic hatred.

I was received very warmly, the people I met were evidently happy to

have Polish observers with them. Older people, who mentioned the Polish

past of the region to me, did it in neutral, if not positive, terms.

People in Vola Kovelska

generally

wanted me to take photos of them. I discussed politics in a friendly

atmosphere with a Yanukovych supporter. I was even invited to eat and

drink vodka with the electoral commission (I accepted meals, and

declined vodka; apparently, drinking vodka with meals is commonplace in

Ukraine, like drinking wine in France).

This is all in line with today's attitude of friendship between

Poland and Ukraine, which is prevailing in both nations. The Orange

Revolution received strong support from Poland, both from government

and from many individuals.

One villager openly expressed hostility towards Poland in front of me. This person was elderly: she probably remembers the time when Ukrainians opposed the Polish government in Volyn. The lady was offended by the fact that Poles supervise a Ukrainian election. She also mentioned Iraq (in Iraq, over one thousand Ukrainian soldiers serve under Polish command).

You cannot see anything flashy or luxurious in rural Volyn. Roads

are

relatively bad, the number and quality of cars is quite low (most cars

are Ladas). But the basic needs of the population are satisfied: people

seem to have enough food, television, and even telephones. To my

subjective eyes, today's Volyn resembles rural Poland just after the

end of

communism (1989), except that rural Poland had very few telephones in

1989. Like Poland in 1989, today's Ukraine is in the process of leaving

behind a corrupt political system, and enters democracy.

The Palace of Culture outside the city, shown on the right, is

a typically Soviet feature of the landscape: it is not conveniently

located (see photo in context), and looks

oversized, but is

highly visible, and, most certainly, this is why it was built (some

Party Secretary must have been incredibly proud, a number of years

ago).

On December 26, Ukraine succeeded in getting rid of massive fraud

that

had plagued the previous vote, and in conducting a truly democratic

presidential

election. This is what international observers generally report (see

here,

here,

here, and here), and this is

what I

observed in Vola Kovelska.

I may add that the I met a very friendly atmosphere.

The electoral procedure did, however, have some flaws. Vote secrecy

was not perfectly ensured. The procedure of "vote with

another person's help" was conducted with little control and no

reporting, making it difficult to rule out undue influence of voters'

relatives. The conditions to meet in order to vote at home were changed

two days before the vote, confusing the voters, and leading to an

inconsistent implementation of the law.

Ukraine will most certainly enact now a new electoral law, and we

may hope that all these points will be properly addressed there. (The

law of December 8, 2004 was temporary, and will not apply in future

elections.)

Regarding vote secrecy, however, procedural improvements are most

certainly not enough: an

educational effort will be needed to ensure that the importance of vote

secrecy is generally understood. Let's not forget that Ukraine has a

long history of Soviet elections, where all democratic rules were

consistently broken; this created bad habits, and I believe

that the lack of attachment to vote secrecy is one of these habits.

The vote at home procedure is probably the most bizarre feature of Ukrainian elections. Although it is not necessarily a bad idea, it is a possible source of fraud, and has Stalinist roots: under Stalin (or generally under Soviet Union), bringing the ballot box to the voter's home was the most certain way to increase turnout, and, additionally, to distinguish between voters who willingly boycott the election (and therefore deserve punishment), and those who are simply sick, drunk, or otherwise unable to participate.

I belonged to one of the many groups of observers sent by Prawo i

Sprawiedliwość (PiS), a Polish political party friendly to

Yushchenko. PiS made it clear that you do not need to be their

sympathiser in order to participate. As a result, PiS card-carrying

members were mixed with PiS opponents, leading to interesting political

discussions in the bus. Some

participants progressively began to dislike PiS

because of the way the trip was (dis)organized. The worst point in the

organization was the trip from Warsaw, Poland, to Kovel. The distance

by road is 330 km, but for reasons I cannot understand we followed a

600 km route through Przemyśl, Poland, then Lvov, Ukraine. Due to

various stops connected with the general lack of organization, the trip

lasted 21 hours. This gives an average speed of 29 km/h, and took as

much time as travelling at 16 km/h (10 mph) through the shortest route

(a slow

bicycle's speed).

I still have some gratitude towards PiS, as a badly organized yet

interesting trip is better than no trip at all. And they even paid me

60 hryvny (10 dollars) to buy food (food is cheap in Ukraine).

Click to see a photo of me (different place, different time).

This document is Copyright (C) 2005 by Marcin Skubiszewski. The images embedded within are likewise Copyright (C) 2005 by Marcin Skubiszewski, except: photo of an Orange Revolution gathering (by Vladimir Ivshin, originally published by Wikipedia) and the map representing election results (by Sven Teschke, originally published by Wikipedia). Redistribution of the document, including all images without exception, is permitted under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License.